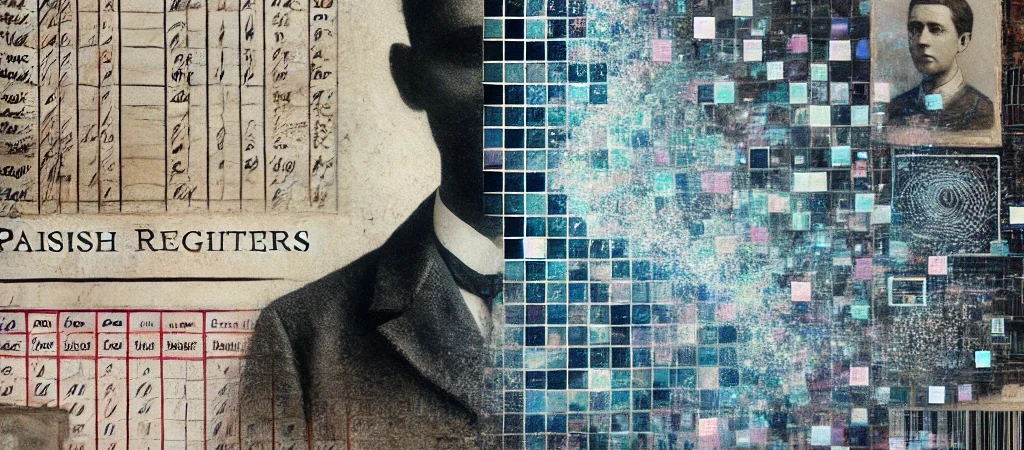

This post is part of Citizen Erased, a 10-part series tracing how recordkeeping shaped identity in Georgian England.

In Part 1 – The Paper People of Lichfield, we questioned whether Acton was a family name or a clerical tool. Part 2 – Throughput by Design investigates how children were entered, processed, and monetized by the parish.

This post dives into bastardy bonds, illegitimacy, and how identity was administratively constructed for throughput under the Poor Law regime, using Lichfield, Staffordshire as the case study.

Assigned by Acton

Illegitimacy, Bastardy Bonds, and the Administrative Invention of Family

When a woman gave birth in 18th-century England outside of wedlock, the event triggered a bureaucratic reaction — not just scandal or shame, but paperwork. And if she was poor, that paperwork could dictate the fate of her child, her freedom, and even her assigned family name.

In Lichfield, we see a clear pattern: dozens of pauper children registered under the name Acton, often with no father listed, and sometimes with generic or absent maternal names. Why? Because the Poor Law didn’t care about who the family was, only that someone — anyone — could be held accountable, or failing that, processed efficiently.

What Was a Bastardy Bond?

A bastardy bond was a legal instrument used by parish officials to recover the costs of raising a child born out of wedlock. It worked like this:

- If a single woman was visibly pregnant or gave birth, she was hauled before the local magistrate or parish vestry.

- She was forced to name the father.

- The named man (true or not) was pressured to accept liability, often paying a bond or regular maintenance.

- If no man could be named, the parish — and by extension the taxpayer — became responsible.

To avoid this, parishes did two things:

- Pressured women to name someone, anyone.

- Assigned the child to a pauper family line already on the books — often a familiar surname like Acton.

Administrative Identity vs. Biological Lineage

If a girl named Mary gave birth in the Lichfield workhouse in 1742 and couldn’t name a father, the child might be baptized “Thomas Acton.” Why?

- The surname already existed in the parish register.

- It was easier to manage legal records with consistent naming.

- It allowed the parish to bury the complexities of illegitimacy in paperwork.

“Acton” became a ledger entry. A tag. A bucket. Not a bloodline.

And once assigned, this identity stuck — through apprenticeship records, marriage banns, and even death entries.

Case Study: Lichfield FreeREG Data

Between 1700 and 1800, we see over 50 entries for the Acton name in Lichfield registers, including:

- Baptisms of children with no father listed

- Multiple burials of infant Actons within the same years

- Several baptisms spaced closely together — but with no known familial link

These names include:

- Rosamond Acton (bap. 1775)

- Richard Acton (bap. 1769)

- John Acton (bap. 1759)

- Jane Acton (bap. 1774, again 1785 — two different girls?)

If these were biological siblings, we’d expect maternal and paternal consistency. But the register shows otherwise. In fact, we often find no parent names at all.

This suggests institutional fabrication: not fraud, but function.

The Role of Overseers and Midwives

Parishes paid local midwives and overseers to monitor and report pregnancies. When a poor woman was seen to be “with child,” especially if unmarried, action was taken quickly:

- Confession extracted

- Father named under duress

- Legal bond arranged — or, lacking that, a parish expense logged

In such cases, children might be:

- Taken into the workhouse

- Assigned to a wet nurse

- Given a name the parish could track

If that child survived, he or she might be apprenticed out under the Acton name — regardless of any biological tie.

What This Means for Genealogy

If you’re descended from an Acton of Lichfield, especially one born between 1650 and 1800, your tree may be administrative rather than genetic. This isn’t bad. It’s real. These children lived, worked, married, and raised families — but under an assigned identity.

Genealogy, in this case, becomes less about blood and more about the mechanisms of state management. Your ancestry might be a map of how society functioned, not just who begat whom.

Larger System: Why It Worked This Way

The reason bastardy bonds and assigned identities were so common was because of incentive structures:

- Parishes were liable for pauper upkeep.

- Pressure from ratepayers to keep costs low.

- Women and children had limited rights.

- Workhouses needed labor and order.

- The Church needed baptisms recorded for legal legitimacy.

And so, a system emerged:

- Women were blamed.

- Fathers vanished.

- Children became case numbers.

And surnames like Acton became the duct tape holding the record together.

Evidence and Sources

- The Workhouse: A Study of Poor Law Buildings in England – Historic England, 1998

- Illegitimacy in Britain, 1700–1920 – Ginger Frost, Palgrave Macmillan, 2016

- FreeREG Transcripts for Staffordshire (Lichfield parishes, 1600–1800)

- Lichfield Poor Law Union Minutes and Apprenticeship Records (Archive Indexes)

- National Archives: Bastardy Bonds and Examinations

What Comes Next

Post 3: “The Actons of Lichfield: Bloodline or Brand?”

We’ll return to the Acton tree — this time questioning whether the lineage from John Acton (1659) to George Acton (1790) is a family, a placeholder identity, or a blend of both.